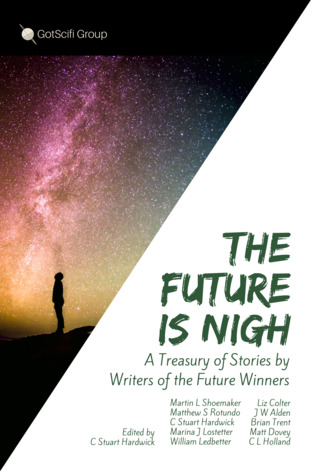

For his new anthology C. Stuart Hardwick has collected

stories by winners of the Writers of the Future contest. As a winner of the

contest himself, he is well-aware of the prestige that goes along with the award.

Each of these writers earned their place on the winner’s stage through the

merits of their writing and their vision; there’s no other way to do it. This

is well-demonstrated in the anthology. The collection of stories is diverse,

and will make a good feast for those whose spec-fic tastes are eclectic. The

stories Hardwick has chosen include some of the softest sci-fi you’ll ever

read, but also much more precise and technical tales, and in between are

stories that are adventurous, thoughtful, artistic and literary.

The collection opens with “Sparg,” by Brian Trent, a

cute/sad short story about the tenacity of a family’s highly intelligent

octopus-like pet, told from Sparg’s own experiences. This gives the story’s

language a simplicity that is reminiscent of a children’s book, which makes a

good framework for Trent to surprise the reader.

Also included is Marina J. Lostetter’s “Rats Will Run,” a

classic that draws on the best tropes from the golden age. It’s an adventure

about science gone wrong, exploration on a deadly alien planet, and ancient

alien secrets waiting to be found. It’s comfortable territory for sci-fi fans;

that’s one of its virtues. Our protagonist, Gabby, is the kind of hero we love to

cheer on: a scientist in the thick of alien wilds on the deadly world of

Cit-Bolon-Tum, where the stakes are just right.

Other stories are more challenging. “Möbius” by J.W. Alden

is a brief tale that doesn’t spend its time on technical descriptions of the

technology that the plot depends upon. It’s a sound choice, since by now we’re

all pre-sold on time travel. Instead, the story cuts straight to the human tragedy,

playing in the depth of the mortal psyche and dragging readers in with it. This

will be a familiar territory to readers familiar with the classics, but it won’t

be comfortable.

Hardwick’s own, “Dreams of the Rocket Man,” a story originally

published in Analog and a finalist for the Jim Baen Memorial Award, is also

featured in this collection. If you haven’t read it elsewhere, this is a great

opportunity to do so. Rare are the stories that lean more on science fact that

science fiction, and provide such vicarious fulfillment to the reader. What

sci-fi reader can’t identify with a child’s desire to launch a rocket as high

as possible? This portrayal of human growth cuts to the heart of why many of us

love science so much in the first place, and being reminded of that is worth

the cover-price on its own.

In addition to those, the collection features six more

stories wherein the chosen WotF winners show off their best. This collection is

polished and smooth, featuring some of the better one-sitting reads I’ve seen

in the past few years. As a reader of anthologies, I’ve gotten in the habit of

forgiving one or two stories for being just

okay, but there’s nothing to forgive here. Every story in the collection

knew exactly what it was doing and how to go about it, some of them so well

that they left me mystified.